The church was founded by a Northumbrian nobleman, Biscop Baducing. Biscop travelled to Rome and France. He stayed there for two years in an island monastery at Lérins, where he took monastic vows, was instructed by the monks, and took on the name Benedict Biscop. Enthused by his experience of the church in Europe, Biscop returned to England. He impressed King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, who provided Benedict with land in 673 to build a monastery. Biscop brought craftsmen and builders from the continent to create a Roman-style church on the banks of the Wear, and it is built between 674-76.

On his visits to Rome, Biscop collected religious, classical, and secular books, with which he established a library at St Peter’s for use by the monks. In 680, the seven-year-old Bede was accepted into the monastery to be a pupil of Biscop.

By the eighth century, there were more than 600 monks in the community and St Peter’s and its twin site at Jarrow were famed throughout Europe as centres of learning and culture, drawing in visitors from across the continent. Around the 730s, Bede wrote his Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin, which is the first substantial piece of English history. It is a crucial document in the formation of English identity and it is fiercely loyal to the Northumbrian kingdom. Bede wrote around 60 books on a variety of subjects, mainly biblical commentaries and interpretation, saints’ lives, and theology. He became known as the Venerable Bede in recognition of his contributions to Christianity.

The oldest parts of the church are the late 7th century west porch (which features a striking and unusual serpent) and the late 7th century west wall of the nave (immediately adjoining the porch). The Saxon tower about the porch dates from around the 10th-11th century.

The interior of the 7th century west wall, showing the original windows near the top before the Saxon tower was extended and covered them.

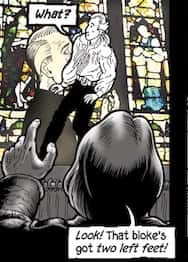

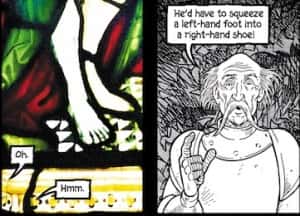

One stained glass window set into the west wall (to the right of the 7th century part) shows a Knight who apparently has two left feet. This may have been the influence behind the Lewis Carroll’s White Knight who similarly complains of ‘squeezing a left-hand foot into a right-hand shoe’. This is shown in illustrations from Bryan Talbot’s Alice in Sunderland.

Images reproduced courtesy of Bryan Talbot.

During the early part of the eighteenth century when the River Wear Commissioners were trying to find ways to make the river more navigable, plans were drawn up to straighten the river at the point where the church stands on a bend. This would have meant the destruction of the church. It was only when the plan proved too expensive that it was abandoned. The church ways also nearly destroyed a century later when it was threatened with being buried under the piles of ballast deposited on the banks of the river at this point. By the end of the nineteenth century, the old cloisters had largely vanished and other buildings – low-quality housing and industrial buildings associated with the shipbuilding industry – reached the Saxon porch of the church. During the twentieth century, these buildings were gradually demolished and from the early part of that century there was a concerted effort to preserve the church.

The church is still used for religious ceremonies today. Its graveyard is no longer used for burials but contains the remains of centuries of Wearmouth residents. Most of the tombstones had fallen into disrepair by the end of the twentieth century and had to be removed. Many of these now stand at the eastern wall of the cemetery. A project in early part of the twenty-first century traced the layout of the long-demolished monastic in stone, and now provides seating and notes of historical interest for visitors.

Sir Cuthbert Sharp’s poem of anguish about a departing sailor is perhaps apt here, too.

The church now stands on Dame Dorothy Street, which is the the main road to the coast in this part of Sunderland. It is one of the few streets named after a woman in Sunderland. The Dame Dorothy in question is Dorothy Williamson, whose life during the English Civil War reflects the changing fortunes of the opposing sides. She left money in her will to help the poor of Monkwearmouth and Old Sunderland. She is mentioned on one of the boards in Seventeen-Nineteen. You can find out more about Dorothy here.