My name is Emma Blackett, trainee teacher with High Force SCITT. I am a mother of four and I have been a teaching assistant for nearly six years in a small rural school in County Durham. Recently, I graduated from Sunderland University with a first in Childhood and Society Studies; but although I have graduated, I am looking forward to still working alongside Sunderland University whilst training to be a teacher.

As I embarked upon the third year of my degree, I found myself contemplating what I would research for my research project. I had previously researched reading for pleasure in my second year and was very much interested in the vocabulary gap in primary school children. Writing, reading and everything it presents and passes on to children is so much more than just a ‘quick story before bed’. From being a young girl, sitting on the chair; lap of my grandad; in the kitchen and in bed, I was read to considerably. This passion has never gone and with the guidance of my supervisor (who recognised this within me) I researched the role and value of the picture book.

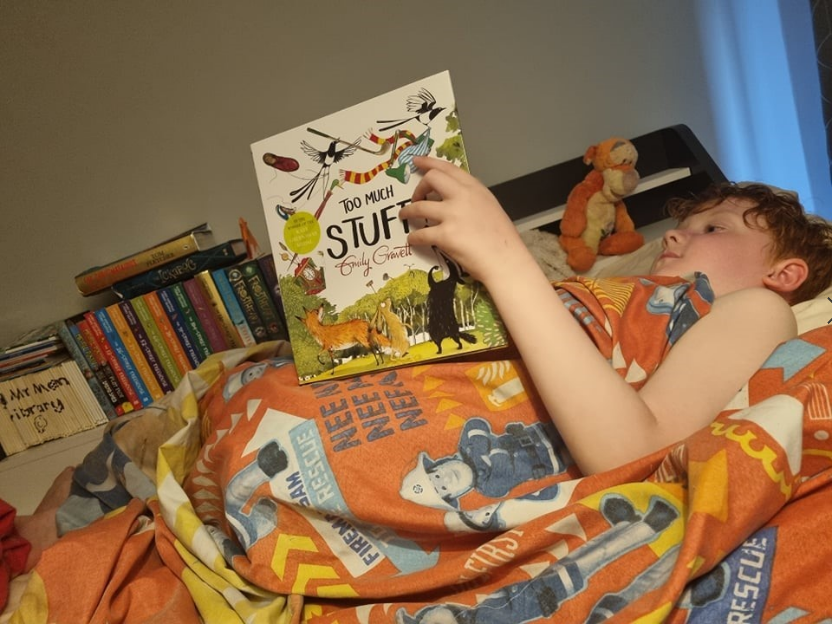

Within my house, my children are surrounded by books, you can see pictured by son below who – still at the age of 7 – loves picture books as much as he enjoys getting snuggled in and reading a chapter book together (currently the BFG). We are surrounded by books. So, as a reader and parent of readers, I thought I knew just what picture books offer children… but can we, as adults, truly understand the world of imagination that children feel when being immersed in a world where anything can happen? Do we forget? Or do we become accustomed to just ‘reading a quick bedtime story’ without really thinking about what children learn from picture books. If we transport ourselves back to our childhood, we may remember what we were read as a child or who read the story, either way it is within these moments in childhood that we build upon the construction of believes and values (Duncum, 2020).

I would like to draw here upon Bruner as his belief that high-quality narrative aids deeper thinking and the construction of knowledge (Smidt, 2011). The author, and illustrator uses interplay between narrative and illustration to create an all-encompassing complex book that requires the reader to be an active agent in the process…. What, therefore, is the role and value? If I think back to last year, before I started my third year, I would have said that picture books allow children the opportunity to develop a rich vocabulary and gives them opportunity to develop a love for books; that those children who have a passion to read are more likely to be better readers, writers and perform academically (Twist, et al., 2007). It is so much more. Picture Books allow for children to develop their emotional literacy and gives adults and children the opportunity to critically engage and question what is happening in the book (Hacking & Vere, 2016). But do we, as adults, see what is really being portrayed in books to be able to question the narrative of the dominant discourse that are with the book?

The story of Farmer Duck by Martin Waddell (that is part of Reception’s reading spine), that I have read multiple times is a prime example: It was not till I dissected the narrative that I saw beyond the words and illustrations. Only then did I see how this story is the narrative of the structural system of society, whereby those in power exploit others to gain exorbitant amounts of profit (Giddens & Sutton, 2017). Without these notions of the dominant discourses within society being questioned and examined, and without the understanding or the time to provide meaningful questioning of, not just social class, but gender, religion, poverty, disability and racism we risk not seeing children as active in the reading process (Kelly, 2009; Arizpe, 2013) and what this means.

Going back to the question posed at the start, do we become accustomed to just ‘reading a quick bedtime story’ without really thinking about what children learn from picture books? I found that through my research project, it was noted that pictures are chosen for a purpose and engaging in critical questioning of the powerful imagery can allow children to see through the eyes of another, whilst relating this to their own lived experiences. However, as a parent I can say that, in the past, I have just read a book without understanding what the message is and, in the rush of the bedtime routine quickly read a story (or…. said, “sorry it is too late”). Finally, as I draw upon my own research, I find myself also thinking about the agency of the child and finish with the question, do we ask our children what they want to read, or do we simply pick on off the shelf because we (as the parent) think that this their favourite book or do we ask them which one they would like? either way it is ultimately the parent who buys the book believing that their child will like the story.

Emma Blackett, Trainee Teacher at Northumbria University

Emma Jayne Louise Blackett | Facebook

Emma is a form Childhood Studies student at the University of Sunderland who achieved a high 1st Class Honours award. Her current focus is writing for publication.

References

Arizpe, E., 2013. ‘Meaning-making from wordless (or nearly wordless) picturebooks: what educational research expects and what readers have to say’. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2), p. 163–176. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2013.767879..

Duncum, P., 2020. Picture Pedagogy: Visual Culture concepts to enhance the curriculum. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Giddens, A. & Sutton, P. W., 2017. Sociology. 8th ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hacking, C. & Vere, E., 2016. ‘The power of pictures’. English 4-11, Volume 56, pp. 13–14. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edo&AN=113283362&site=eds-live&scope=site (Accessed: 15 February 2021)..

Kelly, A. V., 2009. The Curriculum : Theory and Practice. 6th ed. London: SAGE.

Smidt, S., 2011. Introducing Bruner : A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education. Oxon: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Twist, L., Schagen, I. & Hodgson, C., 2007. Readers and Reading: the National Report for England 2006 (PIRLS: Progress in International Reading Literacy Study). [Online] Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/PRN01/PRN01.pdf [Accessed November 2019].